Written exclusively for British Exploring Society.

“In every one of the paddle strokes played the song of the Alaskan wilderness. In every tribal dialect spoken was a thousand years of history passed and in every unseen turn of the river were fear, uncertainty, discovery and learning. Sitting here, near that inevitable finish line, warn and cracked fingers scribble these words with a blunt yellow pencil. The mile wide Yukon River sweeps slowly past me on its last turning leg before draining and widening at the Bering Sea“

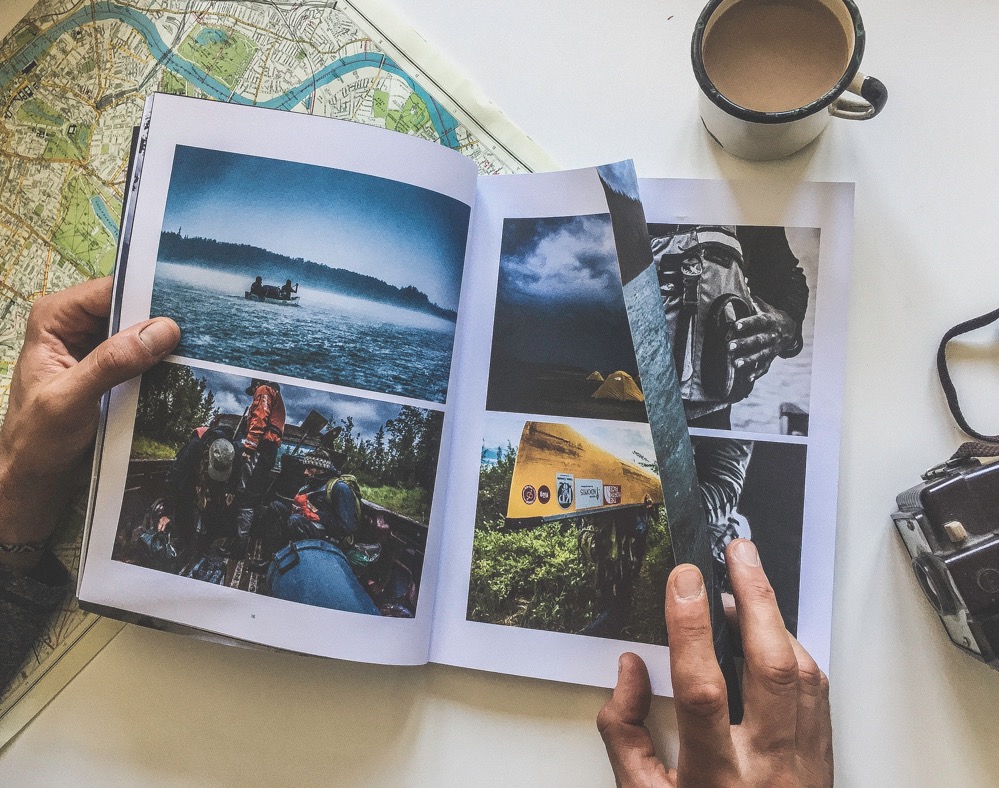

Looking back at these words from my crushed and dog-eared journal, written 67 days into a 90-day canoe expedition, I could never have fathomed the personal impact that such a journey would have. From the very seed and inception of the idea until the day my kit bag crashed back onto the living room floor I’ve been undeniably shaped by the depth and knowledge recieved from such a unique journey. Hard physical experience and remote regions have a habit of teaching you fast but the real lessons came from the intricate conversations with tribal elders and understanding their connection to the world they live in.

Directly from my expedition journal here are four of the valuable lessons taken from Source to Sea.

1. The Power of Generosity

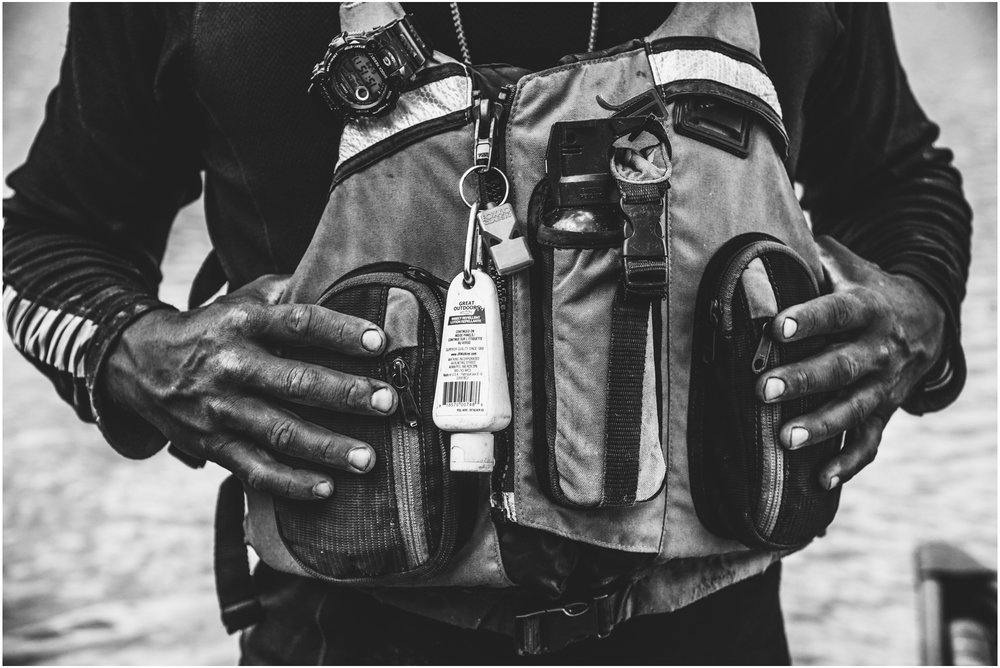

I believe one of the most beautiful facets of the human spirit, in any culture, is generosity. Unbeknown to me traditional customs in the tribal communities along the Yukon dictate that when a visitor is welcomed into a home, regardless of ethnic background or religion, they are treated with a distinct warm friendship and kindness. Also as a mark of respect it is custom to offer the best food available, even when in short supply. What makes this generosity unique is the food and from where it is sourced (nearby forests and rivers) and so precious the message in offering it. To them, this selfless act of giving takes on a spiritual meaning. From community to community, day after day, we experienced this same level of generosity, which only deepened my perception of this special human quality. Ultimately, I found the act of true generosity was in giving time, love and friendship and asking for nothing in return.

2. Wilderness - A Space For Wonder

The Yukon is a powerful place and the river itself is only one part of an immense living ecosystem. The landmass covers over four hundred and eighty two thousand square kilometres with much of the southern region sitting rugged and untamed. Those basic facts alone focus the attention and open the minds door for a wondrous curiosity. The lessons of immersion in such a remote environment ran deeper than the tangible grandeur, vastness and solitude of the wilderness. Such prolonged exposure afforded the time and inspiration to question the inner vastness of our spirit on a human level. Some moments opened my eyes to the immense and cyclical forces around me, yet other occasions showed the delicate intricacies of nature and the passive turning of the seasons. Not only is the wilderness a space for wonder it regularly demonstrates (on a grand and micro scale) the often beautiful and harsh balancing act of the natural world. This alone is magical.

3. Our Connection to Environment and Landscape

All of my expeditions, long or short, involve the story thread of native cultures. Within this there is my search for simplicity, wisdom and a way of life. 1st nation groups have permeated the vast Yukon River region for over ten thousand years and with that their connection to the environment and the wildlife has taken on a spiritual significance. Not only does this sacred relationship govern their way of life, it holds the key to the people and their culture. From conversations with native elders, subsistence fisherman and tribal chiefs I learnt how we as humans still require a living dynamic relationship to the landscape in order to feel connected to something greater than ourselves. And in order to deepen this connection, learning about and living close to the land was the way to achieve it. During one of those conversations I was told, “Once you have respect you care, and when you care you share, once you share you teach” – For me, these are all ways of living.

4. The River Of Life

On those long expedition nights, where darkness never fell, I would sit and be hypnotised by the influence of the river and its inevitable demise. In my journal I would sometimes contemplate how gradually I learnt about the rivers power and complexity. More so I would reflect on how our own human nature and lives subtly mimic the rivers journey. On July 28th 2016 – Day 67 – My journal read:

“Every man and woman has a river running through them. In us all there is a source, where everything begins. As we go through life the knowledge from tributaries, streams and other rivers gently feed into us, increasing confidence and flow. We learn to adjust and navigate as we face life’s rapids and turbulent waters. These obstacles do not cease our river yet they divert its course; the forward movement magnetised by something greater. As the river widens it has the power to give life and death, to move mountains and carve valleys, much as we learn find and follow passions we move the same mountains. At some points on our river the way is unclear and the next turn uncertain. By passing through with instinct and trust we learn to embrace the undefined and irregular. Finally, the once glacial droplet spills into the ocean and two of nature’s greatest forces are combined. Here, the pull of the river and the swell of the sea become a singular force of intricate systems working in tandem, much like us.“